Educating a Mind

Stop teaching mice and start teaching mankind

This is Part 2. For Part 1, see: Teaching Mice, Not Men

In part 1, I argued that the conventional approach to education is not truly aimed at helping students understand what they’re being taught.

Instead, with rare exception, it is aimed at conditioning the student, like training a mouse to hit a button, but for answering trivia questions and plugging numbers into the quadratic formula. To add insult to injury, the conditioning is often abysmal. Shockingly little of the material remains in the average student’s mind past the exam date.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can create an education aimed at learning, understanding and thought. We can design an education that provokes sustained interest, motivation, and joy. We can build an education that empowers meaningful, instead of wasteful, effort.

The key is designing an education around the intellectual capabilities and needs of man.

Respecting a Student’s Mind

The conventional approach may treat students like mice in a lab, but a proper approach treats students like scientists in a lab.

A child is born a scientist — someone who studies phenomena closely, makes discoveries, and forms new concepts that help him understand and explain the world more clearly.

We can observe this in action. We can see how intently a baby tracks his mother’s face or how seriously a toddler explores his environment, needing to pick up and inspect everything in his own hands. A baby, hardly able to see or move, uses tremendous effort to study the world — to focus his eyes; to control the jerky movement of his arms in order to grab the object nearby; to repeat and experiment with sounds in order to master the language that allows him to crystallize his experiences and communicate with his loved ones.

From birth, a child is constantly informing the adults around him of his deep desire and desperate need to see for himself, walk for himself, understand and navigate the world for himself. The child is a scientist; the whole world is his to discover; and he is eager to scale every mountain.

An educational approach that recognizes and respects a student’s scientific mind can capitalize on his eager desire to know everything. What’s more, a good education can even cultivate the student’s natural scientific bent until it becomes his characteristic way of approaching the world.

In this kind of education it would mean, among other examples, that, at the end of a physics class if a student uses a formula, he is not deploying it mechanically; he knows why the formula works and why it’s appropriate to use in that particular context. If the student says, “mitochondria is the powerhouse of the cell”, it’s not just an empty phrase to him; he can give details to explain why the metaphor is apt, and other ways in which the metaphor breaks down.

In his book, A Mathematician’s Lament, Paul Lockhart describes how a mathematician approaches understanding a phenomenon in math which illustrates some aspects of what an educational approach like this — one that respects and cultivates a student’s scientific mind — could look like.1

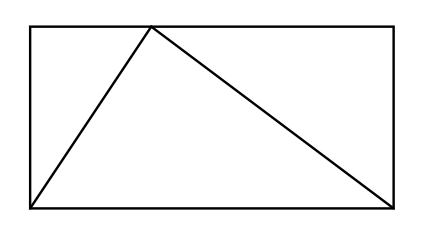

Imagine you’re a mathematician and you want to discover how much space a triangle takes up. You experiment by drawing a rectangle around the triangle. How much space does the triangle take up inside this rectangle, you wonder. Two-thirds maybe? How can you find out for sure?

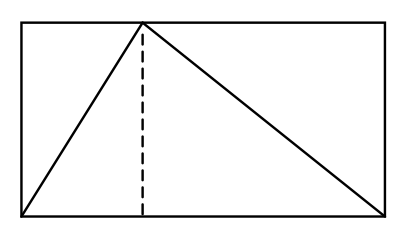

While tinkering with this question, you play with the shapes, form hypotheses, and experiment with different approaches to finding the answer. At some point, you decide to try chopping the triangle into two, like below:

Looking at the shapes now, you notice something shocking. On either side of the dotted line, the triangular pieces are mirror images of one another, reflected across their shared diagonal line. There is just as much space inside the triangle as outside — the triangle takes up exactly half of the space inside the rectangle!

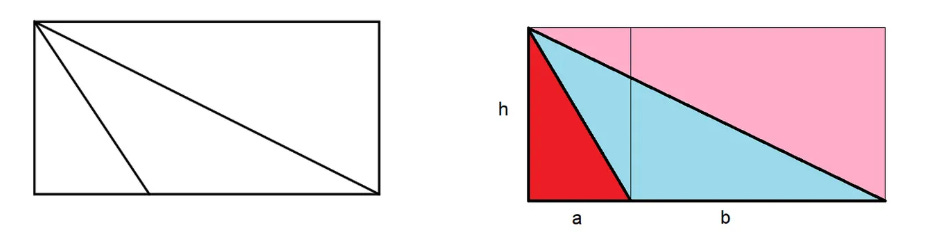

Propelled by your discovery, you rush to test and experiment further. You push yourself to refine your understanding. You experiment by drawing other triangles, ones that clearly don’t take up half the space inside the rectangle, and then try chopping up the triangle in new ways to form helpful new visual models . . .2

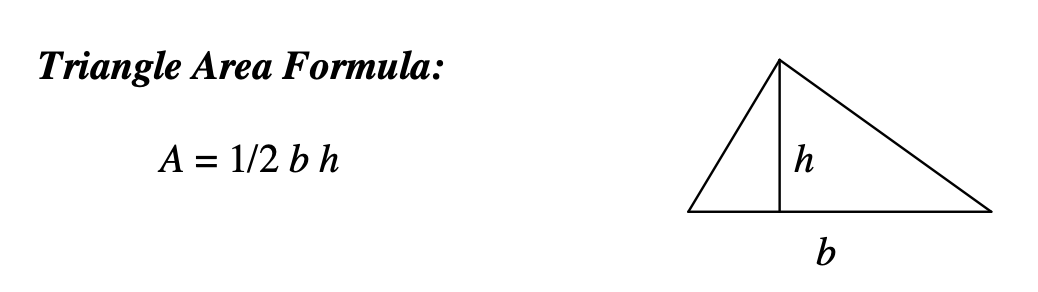

. . . until eventually you convince yourself of a profound conclusion: “The area of a triangle is equal to one-half its base times its height. And, in the special case where the triangle’s base and height are the same dimensions as the base and height of the rectangle you draw around it, then the triangle also takes up exactly half of the space inside that rectangle.”

Lockhart contrasts the mathematician’s approach with the conventional approach used in school this way:

…it is so heartbreaking to see what is being done to mathematics in school. This rich and fascinating adventure of the imagination has been reduced to a sterile set of “facts” to be memorized and procedures to be followed. In place of a simple and natural question about shapes, and a creative and rewarding process of invention and discovery, students are treated to this:

“The area of a triangle is equal to one-half its base times its height.” Students are asked to memorize this formula and then “apply” it over and over in the “exercises.” Gone is the thrill, the joy, even the pain and frustration of the creative act. There is not even a problem anymore. The question has been asked and answered at the same time— there is nothing left for the student to do.3

When a student is not permitted to use his scientific mind to learn, when he is not allowed to study phenomena, to see the need to ask questions, to recognize and then struggle to overcome contradictions — what happens? What is left for him to do? Without “the thrill, the joy, even the pain and frustration of the creative act”, what is left of the experience of “learning”?

All that is left is exactly what you see in a typical classroom: stultifying, mind-numbing boredom. The students sit in class after class, hour after hour, geese being force-fed, mice running mazes, seals clapping on command.

“Everyone knows that something is wrong [with our present system of education]”, Lockhart summarizes.

The politicians say, “We need higher standards.” The schools say, “We need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, “Math class is stupid and boring,” and they are right.4

But why exactly does an approach aimed at understanding — an approach that recognizes and respects a child’s scientific mind — lead to a more joyful, engaged, motivated learning experience for students?

For this, we need to look again at the nature of a child’s scientific mind, but this time from the perspective of the needs of human life.

Respecting the Role of Knowledge

Think again of the toddler which we can observe expending massive amounts of effort to walk, to grasp things with his hands, to talk, to discover things for himself . . . why is he doing all this? Why is he not happy to rest easy, to be waited on hand and foot? Why does he protest so stridently and grieve so dramatically when adults take over and do things for him?

Or think of the rare kind of adult who has a similar level of curiosity and ferocious independence as the average toddler — a dedicated scientist, engineer, or founder. Why do they spend years and years working, often from dawn to dusk, to understand some facet of reality better, or on bringing a new invention or company to life?

Why would Galileo risk burning at the stake rather than recant what he knew to be true? Why would Archimedes be more concerned about the disturbance of his diagrams, than the Roman soldier, part of a force besieging and sacking his city, entering his home and threatening his life?

The attitude of both the average young child and the remarkable scientist reflects something true for everyone: reaching clarity about the world, gaining new knowledge and new understanding, is vitally important and valuable for life. Knowledge is the very thing that makes human life possible.

For the young child, knowledge about the world is a critical need. The child enters the world knowing nothing about it, unable to communicate his needs, unable to make sense of the chaos around him, barely able to see. Gaining knowledge, for him, is the difference between experiencing life as an overwhelming and terrifying mystery, and experiencing life as logical, predictable, and delightful.

In any domain which we want to thrive — in our careers, our relationships, or our leisure — it is gaining new knowledge and new clarity that makes each successive level of success and happiness possible. And for society as a whole, it is the discovery and application of new knowledge at scale that has made our unprecedented standard of living possible.

In sketch, this is just what human life is — from finding the cure for polio, to inventing indoor plumbing, to mastering a new dish for date night, to house-training a recalcitrant puppy — successful human life just is the new discovery and active-minded deployment of deeply understood knowledge.

When education respects the student’s scientific mind, when it helps the student understand what is being taught, it allows a student to experience the undeniable value of knowledge to human life, here and now.

The world’s most elite educators do this every day. Each month, these educators attract millions of engaged learners by helping them experience knowledge as valuable: on YouTube.

Take this example: why would 17 million people watch the video, “Hexagons are the Bestagons”?5

From the moment you read see the title and thumbnail, this video presents the viewer with an intriguing mystery. It prompts the viewer to ask: why would anyone argue about a polygon? What reasons could there be for being so passionate about hexagons of all things?

From the opening hook — it’s because of bees?? — the video then promises there will be a compelling answer to the mystery. It promises that, if you know more about hexagons, you will not only understand the presenter’s reasons for caring, you will start to see the whole world in a brand new light: from honeycombs and the cells in your eyes, to snowflakes and pencil “lead”, to aircraft wings and the hexagonal cloud of Saturn.

It is this experience of seeing connections opening up before you, of some new facet of reality coming into focus, that makes learning feel meaningful, engaging, and motivating.

Of course, a person will not walk away from this video as an expert in hexagons or any of the other topics presented. One video is not a curriculum. It takes a lot of time and work for any concept to be fully understood and mastered, and any approach to education would need to include strategies and activities to help a student achieve long-term memory.

But this video provides an illustration of how an educational approach aimed at understanding treats knowledge.

Knowledge for Men, Not Mice

In the conventional approach to education, knowledge is treated as something static. There’s a fact — Vasco da Gama sailed around Africa to reach India in 1498 — and if a student can recall this fact when prompted, this is evidence of having acquired “knowledge”.

In the best case, when the conventional approach actually works to help a student remember what is taught, the student gains something. He gains inert information that he stores mentally and can dredge up when prompted, like taking a book off a bookshelf or pulling up a file from a computer’s memory.

But if knowledge is supposed to be a tool for life, then the best version of life a student is prepared for with this kind of education is the life of a perpetual Jeopardy! contestant. For this student, knowledge is a tool for life, but only a single-application tool like a hole-puncher. He can use this tool in constrained contexts, and the closer the situation and context in which he was taught — like a homework question that copies the format of his notes exactly, or a standardized test with multiple choice answers — the better, but he can go no further.

By contrast, an educational approach aimed at understanding treats knowledge as something dynamic. It cannot be handed to a student wrapped in a bow. It must be earned by the student himself. In this approach, knowledge is the end result, the solution at the end of a long cognitive process the student has undertaken.

If knowledge gained in the conventional approach is a single-application tool like a hole-puncher, knowledge gained in a proper education is a multi-purpose tool like a Swiss army knife. It lends itself to ever more connections, applications, integrations, and questions. It is knowledge that prepares a student for the full, complex, dynamic life of a human being.

A student who understands that multiplication is just successive series of addition can figure out the answer to a multiplication problem he’s never seen. A student who only memorizes the multiplication tables without understanding how it works would be at a loss when presented with a problem he hasn’t memorized.

An education that respects a student’s scientific mind and cultivates real understanding, necessarily involves memorization of facts, figures, and formulas, but it is not synonymous with it. “Memorization”, though maligned as education’s most devilish boogeyman for over a century, is actually a neutral concept. To evaluate whether a given case of memorization is good or bad for a student, or for the learning process more broadly, one must look at the nature of what one is committing to memory and for what purpose.

Are you committing to memory something you truly understand, something that you want crystallized, made easier to use and hold and take with you on any future intellectual task you embark on? Or are you committing to memory something you don’t understand, a meaningless slogan you recite on cue, an out-of-context piece of trivia that represents a dead-end in one’s thinking, an incomprehensible algorithm you enact without knowing why or how it works?

The difference between these two kinds of memorization is the difference between a mind nourished and a mind crippled. They cannot be treated as one and the same phenomenon — to be touted or condemned, one and all.

As a field, education has barely made its way out of its equivalent of the Stone Age or the bloodletting beds. There is a desperate need for innovation, engineering, curriculum development, and new philosophic thought.

Many of the details of a better approach to education, one that respects the child’s scientific mind and the role of knowledge in human life, will take new thought and experimentation to work out — at different levels of education, for different subjects, with different and better implementations of new technologies.6

Maria Montessori began this work, predominantly in early childhood, starting in the early 20th century. Her contributions are monumental. She not only developed an approach that respects the child’s mind, but an extensive and rigorous curriculum that helps a child deeply understand concepts, memorize at the right stage in the learning process, and develop impressive knowledge at an early age.

In Part 3 of this series, we will do a deep dive on Montessori, just from the perspective of its approach to respecting a child’s scientific mind and thereby helping children achieve deeply understood knowledge.

Lockhart would likely object to me categorizing this example under the heading of “science”. In his book, he is using it as an example of how math is like imaginative play and art. My view, however, is that the process he describes is scientific — it’s the close study of a phenomenon, an abstract phenomenon in this case, where he asks questions, experiments, looks for contradictions etc. in order to come to a new conclusion. Lockhart is reluctant to tie this to science because he has a (to me, tragic and improper) disdain for science and “practical” knowledge.

The area of the blue triangle of interest is the same as the area of the pink triangle minus the area of the red. Further, the area of the pink triangle is exactly half of the large rectangle, and the area of the red triangle is exactly half of the mini-rectangle created when the blue triangle is chopped up as shown in the diagram. Thus, the area of the blue triangle can be calculated:

A_blue = A_pink - A_red

A_pink = 0.5(b+a)*h

A_red = 0.5a*h

A_blue = 0.5(b+a)*h - 0.5ah

A_blue = 0.5bh + 0.5ah - 0.5ah

A_blue = 0.5bh

Lockhart, Paul. A Mathematician’s Lament: How School Cheats Us Out of Our Most Fascinating and Imaginative Art Form (p. 18). Bellevue Literary Press. Kindle Edition.

Lockhart, Paul. A Mathematician’s Lament: How School Cheats Us Out of Our Most Fascinating and Imaginative Art Form (pp. 12-13). Bellevue Literary Press. Kindle Edition.

YouTube is the world’s best, and least recognized, EdTech. There are so many amazing content creators on YouTube creating elite educational material. (For just a small taste in addition to the example in the piece, check out: VSauce, Smarter Every Day, Tom Scott, Wendover Productions, Veritasium, CrashCourse Science/History, LindyBeige).

Check out some of Dan Meyer’s work on math: e.g. his TED talk “Math Class Needs a Makeover”, and his blog “MathWorlds”